Constructing the Water Supply Network in France: The Era of Beginnings

For centuries, aqueducts and fountains mobilized significant capital without necessarily prioritizing universal access to water. Water was scarce, but it was not a primary concern. These constructions were symbols of political prestige and had to be monumental and visible. Inequalities in access to water marked social distinction, which was also reflected in the ability to drink mineral water. In the eighteenth century, no less than thirteen different types of water were sold by the pint in Versailles, not including the fountain reserved for the royal family, and there were twenty-two types available in Paris.

While their invisibility made them less spectacular, water distribution networks brought about a considerable change. While a local water supply through conduits could be ensured by multiple small companies, only national and soon international companies had the technical and organizational capacity to implement these networks on a territorial scale.

Grégory Quenet

From Water Carriers to the First Potable Water Networks: A Revolution in Progress

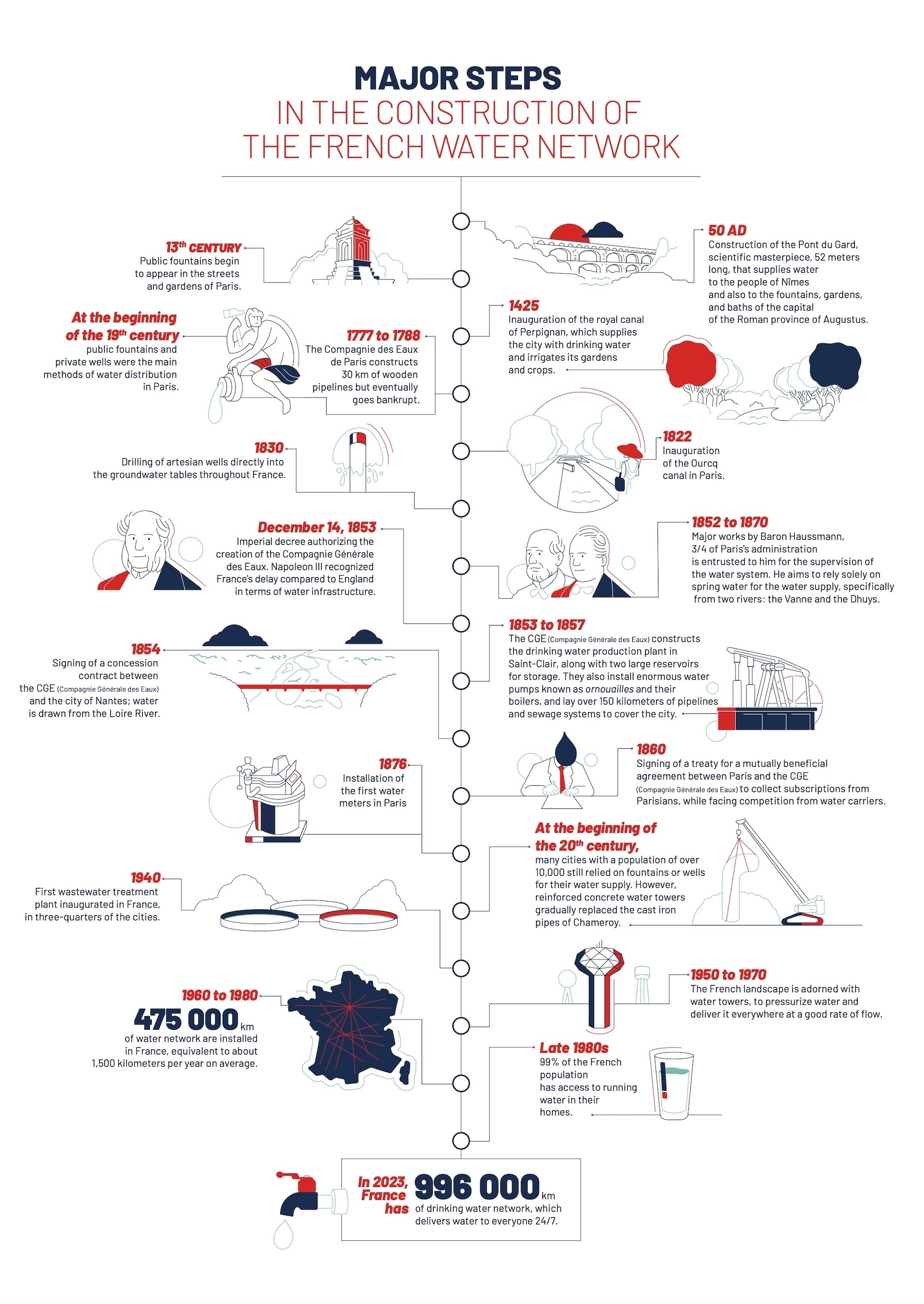

The nineteenth and twentieth centuries brought about a complete revolution in water distribution across Europe. It was an development unprecedented since the time of the Romans! The transition from a straight-line model based on Roman aqueducts to a network that served multiple points without hierarchical ordering was a true revolution, driven by individuals motivated to bring progress to their fellow citizens.

From water carriers to public fountains and eventually the widespread adoption of water treatment, water became accessible to everyone within two centuries. The daily lives of more and more of the French were improved until access eventually expanded to encompass the entire population in the second half of the twentieth century. It was during this time that potable water finally began to reach the households of individuals directly, both in urban and rural areas. To achieve this feat, it was necessary to source, store, and transport water, utilizing techniques made possible by the engineering achievements and the political and entrepreneurial will of the pioneers of the Compagnie Générale des Eaux (CGE). This immersion into two hundred years of water history has shaped our practices and our society.

While the nineteenth century indeed marks the beginning of the major water distribution revolution in France, it builds upon centuries of technical innovations. From the dawn of humanity, the search for water sources has been crucial. As early as 6,000 BC, well before the advent of writing, the first wells were established. Water was no longer a resource that could only be obtained directly from a river; effort was required to extract it for use in the same location where it was drawn. Over time and through the centuries, increasingly sophisticated techniques were developed by the early engineers.

As one must render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s, credit must be given to the Roman engineers for the remarkable feat of systematizing water distribution to a larger population. Symbolizing the power of the Empire, water became a central element of daily life in Ancient Rome, supplying water to hundreds of thousands of inhabitants through an ultra-sophisticated hydraulic system. The famous aqueducts allowed water to be brought into cities for consumption, while an ingenious sewer system carried away wastewater, sweeping through latrines and converging towards the Cloaca Maxima. This extensive canal, serving as a collective sewer, fulfilled three functions: collecting rainwater, disposing of wastewater, and sanitizing the marshes. It remains the oldest drainage system still in use today, as the ancient conduits continue to carry rainwater and debris away from the Roman Forum.

In France, the Pont du Gard exemplifies the legacy of Roman engineering ingenuity. Built in the first century AD, this aqueduct carried, at the height of its glory, 35,000 cubic meters of water each day from Uzès to the city of Nîmes. This scientific marvel, spanning fifty-two kilometers, supplied potable water to the people of Nîmes, as well as to fountains, gardens, and the baths of the provincial capital under Roman rule. These fountains remained fundamental to water supply in cities until the Middle Ages.

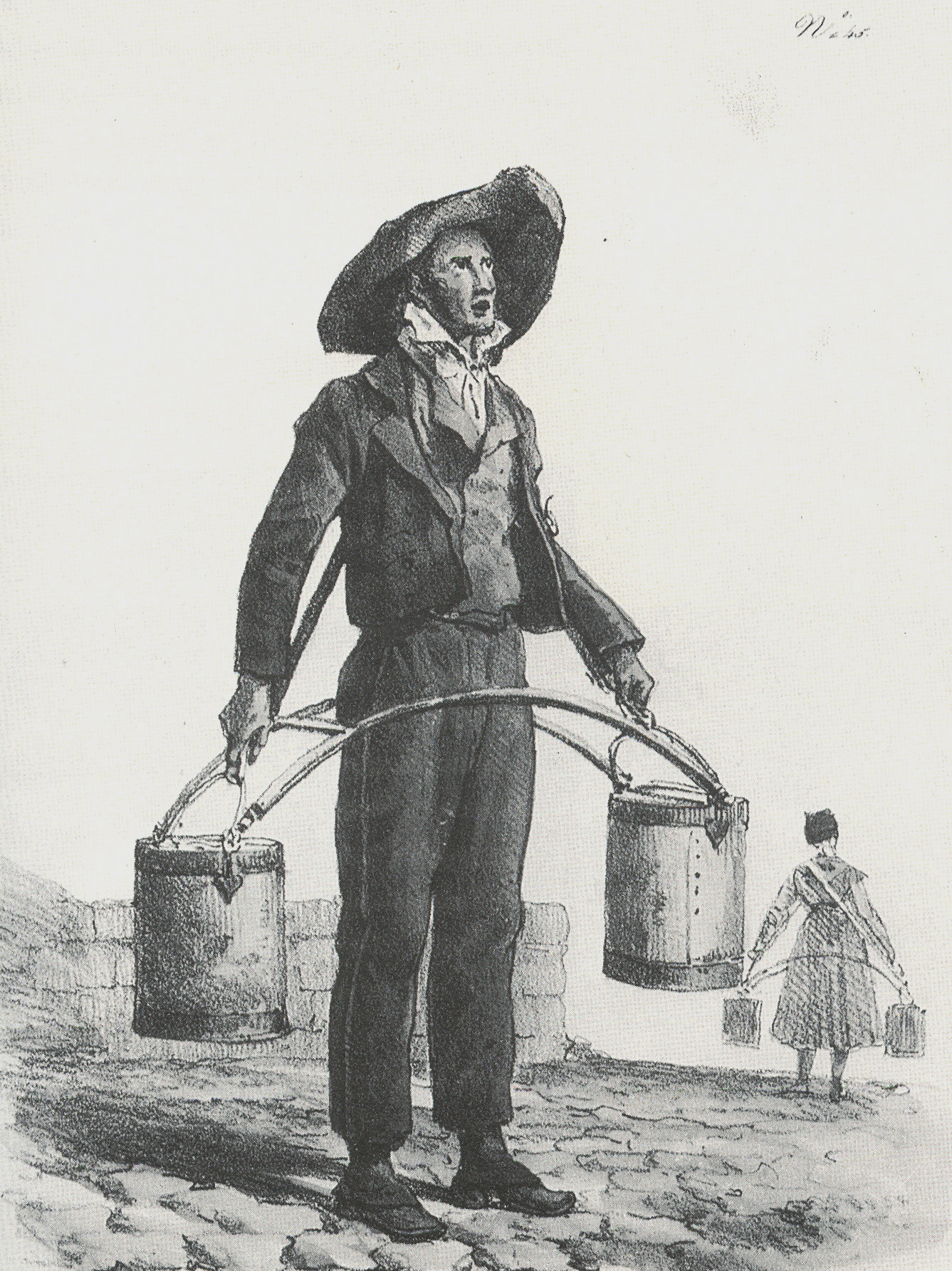

Although at that time the concept of sanitation was often neglected, new hydraulic pipelines allowed for the large-scale distribution of water. From the thirteenth century onward, the fountain system developed and provided drinking water directly to cities. Under the Ancien Régime, public fountains multiplied and became accessible to a wide audience. To transport water directly to houses or to the upper floors of buildings, the wealthier individuals employed water carriers. As the number of fountains increased, so did the number of carriers, who sold their precious commodity by shouting “water, water!” In his work Le tableau de Paris, published in 1781, writer and journalist Louis-Sébastien Mercier explains that a skilled water carrier could make up to thirty deliveries a day with his two buckets, each delivery representing approximately 25 liters, for up to 750 liters per day.

The Water Carriers

The water carriers delivered water from public fountains directly to the more affluent population’s homes, charging two sous for delivery to the first or second floor and three sous for higher floors. The bourgeoisie, meanwhile, sent their maidservants to fetch water from the fountains, which often led to conflicts between servants and water carriers. In 1698, the water carriers obtained exclusive access to the fountains.

In Paris, their numbers increased from a mere fifty-eight at the end of the thirteenth century to twenty-nine thousand by the end of the eighteenth century. The water carriers were equipped with a leather strap placed over their shoulders, with hooks attached at each end to hang the buckets. nineteenth-century literature and serials frequently highlighted the Auvergne origins of these deliverymen, as Auvergne was a major source of emigration to the capital. They could earn up to three thousand francs per year, provided they made thirty deliveries of twenty-five liters per day.

They sourced water from the receivers, whose task was arduous, while the owners of commercial fountains, whether individuals or filtration companies, made a good living: “presence from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. (sometimes earlier and later), on-site water delivery, record-keeping, price collection, registration of water carriers, recording delivery times, etc.”

Their profession became even more essential as the quality of well water gradually deteriorated, making it unsuitable for cooking or personal hygiene. The workload of those shouting “water, water!” increased when most wells were sealed off and access to fountain water became increasingly necessary.

It was during the Second Empire, with Haussmann's urban renovations in Paris and the implementation of water supply systems in cities, that the profession gradually disappeared, overshadowed by the establishment of water networks, in which engineers from the Compagnie Générale des Eaux played a significant role. By the eve of the First World War, water carriers no longer existed.

Another way of bringing water to city dwellers was through canals, such as the Canal de Perpignan, built in 1423 and filled with water in 1425. “The royal canal of Perpignan, which is celebrating its six hundredth anniversary, was primarily intended to supply the city with drinking water. But it also served to provide irrigation water for the city's gardens and crops, supply the six mills along its route, and provide water to the “ulls” —circular water intakes installed on the canal, whose diameter was theoretically standardized to allow for maximum water flow in order to irrigate the authorized lands of Roussillon,” writes Dylan Planque, a doctoral student and author of a thesis on the Perpignan canal.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, public fountains and private wells were the main methods of water distribution in Paris, as well as in other major French cities. Following the French Revolution of 1789, the demand for water increased due to the number of people leaving rural areas for cities. It then became urgent to review the water distribution system in France. And for the French engineers of the time, there was an example to follow: that of the United Kingdom, and London in particular. The capital of the British Empire benefited from a sophisticated distribution network that allowed water to be delivered directly into many households. This service was operated by several private companies that shared the London territory. According to Charles-François Mallet, chief engineer of the Imperial Corps of Bridges and Roads, one-third of London dwellings received water on the upper floors as early as 1830. In Paris, the situation was quite different. However, an attempt was made between 1777 and 1788 with the Compagnie des Eaux de Paris, which managed to build thirty kilometers of wooden pipes. Unfortunately, the company went bankrupt and was taken over by the city.

© Régie des Eaux Perpignan Méditerranée Métropole

To offer Parisians a service similar to that of Londoners, French engineers from the Corps of Bridges and Roads took inspiration from the English model and began the water supply works from the Ourcq River in the mid-1830s, supervised by Louis-Charles Mary. The canal, inaugurated in 1822, supplied water in abundance to the city of Paris. Throughout the country, artesian wells1 were also dug directly into the groundwater tables to meet the growing demand in cities such as Tours, Paris, Saint-Denis, Mulhouse, as well as Strasbourg, La Rochelle, and Perpignan.

However, this activity was not sufficient for the engineers of the time. Those from the Corps of Bridges and Roads and the Polytechnique worked toward establishing real water distribution networks in major French cities. It should be noted that the concept of a network itself influenced their thoughts and actions. This concept emerged from Saint-Simonian thinking2 which considered networks to be the beginning and end of social progress. Dominique Lorrain, a research director emeritus at the Centre nationale de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), confirms this: “At that time, cities were being transformed through networks: railway networks, transportation, electricity, domestic gas, and water distribution.”

The General Water Company, at the Heart of Major Construction Projects

In this context, on December 14, 1853, Napoleon III, who, during his years in exile, had witnessed England's advancement in water distribution compared to France, affixed his signature to an imperial decree authorizing the creation of the General Water Company.

It was the responsibility of the Minister of Agriculture, Commerce, and Public Works, Pierre Magne, to oversee the development of the company. His supervision over agricultural affairs was not unrelated to the mission entrusted to him: even before water distribution in cities, the primary purpose of the new company was the irrigation of fields. In line with the productive logic that drove the first industrial revolution, the main intention of the founders, from Count Siméon to the Duke of Montebello, was to make agricultural lands cultivable and productive that were not yet so. “In 1874, the hierarchy of the two activities would have been reversed,” notes Christelle Pezon, a lecturer at the Conservatoire nationale des arts et métiers (CNAM), even though the company still operated in the Nice region for a few more years: the model of agricultural irrigation could not withstand competition.

Even before the Emperor's official authorization, the assurance of a water distribution contract in the city was the announcement of the company's success. However, contrary to the company’s initial ambitions, the contract would not be in Paris: regardless of the delays faced by the French capital, Baron Haussmann and the engineers from the Ponts et chaussées assigned to the technical services of Paris did not see the benefit of a private concession to accelerate the deployment of the water network. It would be in Lyon, the capital of the Gauls, that the CGE would sign, on August 8, 1853, with the approval of the Municipal Commission on September 17, the world's first concession for public water services.

Prosper Enfantin, Entrepreneur of the Common Good

Born in Paris on February 8, 1796, Prosper Enfantin was one of the early administrators of the Compagnie Générale des Eaux and played a decisive role in its beginnings, particularly in obtaining its first contract in Lyon. He embodied an era and a vision of capitalism, one shared by a large number of enlightened industrialists in France of the mid-nineteenth century: Saint-Simonism. More than just a symbol, Prosper Enfantin was one of its leading figures.

Dubbed “Father Enfantin” in the early part of his life, he came from a bourgeois family. As a student at the École Polytechnique from 1813, where he met future followers of Saint-Simonism, he participated in the Battle of Paris in March 1814 to defend the Napoleonic Empire against European Allies, which led to his expulsion from the prestigious school.

At the age of 18, he found himself in various jobs such as a wine merchant in Germany, Russia, and the Netherlands before returning to France in 1822. During that time, Prosper was initiated into the social and economic theories of Saint-Simon, eventually becoming one of the major figures of this pre-socialist movement after the founder's death. And he'd prove to be as brilliant as he was adventurous.

Known as the “Messiah,” he embarked on a search for the “female Messiah” and conceived the construction of the Suez Canal, a project that eluded him and was ultimately realized, thanks to his technical data, by the diplomat and entrepreneur Ferdinand de Lesseps.

Upon his return to France after further adventures, he settled in Lyon, where many Saint-Simonians had gone to experience the proletariat. The revolutionary mellowed but did not abandon his principles; rather, he put them into practice and began building networks. He participated in the creation of the Union for the Paris-Lyon Railways in 1845, where he was appointed Secretary General. In 1853, at the age of 57, Prosper Enfantin, whose mother died in Paris during a cholera epidemic, became an administrator of the recently established Compagnie Générale des Eaux. Writer Maxime Du Camp described him as “older than his age,” and “weary,” while noting his “attractive simplicity and kindness.”

Regardless of appearances, he mobilized his extensive network—the philanthropist earned admiration from Victor Hugo and Lamartine—to finalize negotiations with the city of Lyon, which had made water distribution one of its priorities. Thus, his aspirations took shape, and networks were established to bring progress to society.

Saint-Simonism was a broad doctrine encompassing social, economic, political, philosophical, spiritual, and, under the influence of Prosper Enfantin, even mystical aspects. It asserted that people should view themselves as brothers, elevated their association as a principle, and called on them to transcend their individual interests in the name of the common good.

It made industry the essential agent of social progress, capable of mobilizing science to guide society toward physical, moral, and intellectual improvement and to make people as happy as possible. With a blend of mysticism and industrialism, this doctrine supported the idea that networks such as canals and railways served universal understanding, and that these physical connections, by facilitating relationships between individuals, could replace conflicts.

To spread this conception of progress, Prosper Enfantin led two newspapers, Le Producteur and Le Globe, and gathered around him a community of around forty disciples, governed by their own codes and rituals, such as wearing jackets that buttoned in the back to emphasize interdependence. This led to his imprisonment for one year for public moral outrage and illegal association, during which time he sympathized with the prison director. Upon his release, he went into exile in Egypt with some of his close followers.

Beyond his professional activities, Prosper remained driven by the Saint-Simonian utopia until the end of his life. In 1860, he founded the Société des amis de la famille, which, thanks to donations from wealthy individuals, provided free medical care, helped the unemployed find jobs, and offered retirement benefits to individuals over the age of 60. Father Enfantin passed away on August 31, 1864, and was buried in the Père-Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

The engineers of the company demonstrated remarkable speed in building the city's network. “In just four years, the General Water Company constructs two large reservoirs, installs three enormous steam pumps (known as Cornish pumps) and their boilers, lays seventy-eight kilometers of pipelines, twenty kilometers of sewers, and one hundred twenty water fountains,” explains Robert Jonac, from the association L’eau à Lyon & la Pompe de Cornouailles. Monumental fountains, from Place des Terreaux to Place Bellecour, including Place des Célestins, were inaugurated to embellish the city and celebrate the arrival of abundant water. All these infrastructures rapidly changed the appearance of the regional capital's water supply, freeing it from the “secondary role, the relay role imposed by Paris,” to borrow the words of Fernand Braudel in his book The Identity of France.3

In practice, water was drawn from galleries and filtering basins supplied by the Rhône and the Saint-Clair drinking water production plant, built as early as 1854. These two reservoirs, with a total capacity of sixteen thousand cubic meters, supplied different neighborhoods of Lyon with drinking water. The filtered water was then pumped by three large steam-powered machines, named Cornish pumps. Developed by Scottish engineer James Watt, “these pumps were used in England in the county of Cornwall in the tin and lead mines, hence their nickname,” explains Robert Jonac.

The vital resource was then distributed through a network of pipelines, and residential buildings were gradually connected to it. Granted, tap water was now subject to a fee, unlike public fountains, but its cost was much lower than that charged by water carriers. Thus, a less affluent population, including the silk weavers known as the “canuts”, could subscribe and benefit from this fundamental innovation.

In another part of the country, in Nantes, the situation also became urgent: the city had only one public fountain for every hundred thousand inhabitants. A concession contract was signed in 1854, and the General Water Company began to draw water from the Loire, upstream of the city. While some Nantais remained skeptical because “residents who are accustomed to paying the water carrier with their daily delivery do not really perceive the savings when offered a monthly billing"4, many of them subscribed to “domestic tap” subscriptions, and the city became cleaner thanks to the “sprinkling” of streets and boulevards.

A few years later, the company also intervened in Nice to modernize the water network when the municipality did not have the necessary funds. CGE diversified the sources of supply and improved the city's sanitation, strengthening its reputation as a tourist destination and its attractiveness to the English to the point that the waterfront became known as the “Promenade des Anglais.”

After initially constructing the Sainte-Thècle aqueduct to transport spring water and the Bon Voyage tunnel-reservoir for storage, they later built the iconic Vésubie canal to meet the needs of the growing population. The canal had three purposes: “irrigation of the hills and serving the municipal irrigation system, providing drinking water to the city of Nice, and supplying the coastal towns east of Nice, toward Monaco and Italy.”5 Nice became a symbol of these French coastal cities: ahead of their time, with a modern water network connected to the railway system, benefiting from the presence and influence of the English, who enjoyed it as a holiday destination and investment opportunity. In Arcachon, where CGE also spearheaded the development from 1882 on, the parallel between the water network and the railway system was taken to the extent that “a pipeline of more than sixteen kilometers followed the Cazaux to La Teste railway line.”6

Back in Paris, Baron Haussmann eventually gave the company his confidence. Under Napoleon III, he had not waited for the company to launch the major transformation works of the capital. To revolutionize the water system, he relied on hydrology specialist engineer Eugène Belgrand. A proponent of “only spring water for supply,” as Christelle Pezon specifies, he ensured that Paris was supplied with water from two rivers: the Vanne and the Dhuys. Heavy investments were then devoted to water distribution in the capital. Over 153 million francs were invested in water supply and sanitation between 1852 and 1870. In total, 842 kilometers of new conduits were built, in addition to the existing 705 kilometers. In the midst of this transformation, in 1860, the Compagnie Générale des Eaux became a government contractor to the city of Paris for two major reasons. The first is that the company had expanded to the outskirts of Paris by acquiring the Compagnie des Batignolles, the Compagnie de Montmartre, and the Compagnie d'Auteuil. When Paris integrated these municipalities in 1859, it sought to unify its networks and therefore had to negotiate with their owners. The second reason was that the city saw an opportunity to entrust a third party with the task of soliciting new customers and facing competition from water carriers. “It is not enough to bring good groundwater into Paris's network to surpass the quality and price of the water carrier service, [...] it is also necessary to engage in a real street fight with them to ensure that customers connect to the public network.”7

A little later, the company also took on the role of commercial services, being responsible for meter reading and billing. These devices, introduced optionally in Paris in 1876, would revolutionize the way people accessed water on a daily basis. To understand why, we must delve into how one subscribed to water supply services before the development of these devices. A subscription to the “gauge” provided a fixed quantity of water per day to subscribers, who filled their tanks in the courtyard of the building (as water did not directly reach their premises). The “flat fee” subscription or “open tap” allowed a person to receive an unlimited amount of water directly at home based on a fixed fee. The water meter changed the game with a simple idea: payment based on consumption. Konstantinos Chatzis, a researcher in history specializing in the history of modern engineers, points out that with the development of water meters in Parisian buildings, “the price had to be proportional to the quantity consumed.” From then on, all French people were treated equally: they had access to abundant drinking water at home and directly paid for what they consumed.

While the hydraulic situation in the capital and in some cities had progressed significantly by the end of the nineteenth century, disparities remained pronounced between different French municipalities, especially between urban and rural areas, at the beginning of the twentieth century. Christelle Pezon’s book, Le service d'eau potable en France de 1850 à 1995, says that at the beginning of the twentieth century, “148 cities with over 5,000 inhabitants had only fountains or wells.”8 In rural communities, home water distribution was virtually non-existent, as “water distribution networks did not reach the countryside in the nineteenth century,” Pezon says. It would take the Trente Glorieuses (the period of economic growth in France from the 1940s to the 1970s) for rural areas to access tap water: in the early 1940s, only 25 percent of rural areas had access to domestic drinking water.

Between Rural Modernization and Urban Demographic Explosion

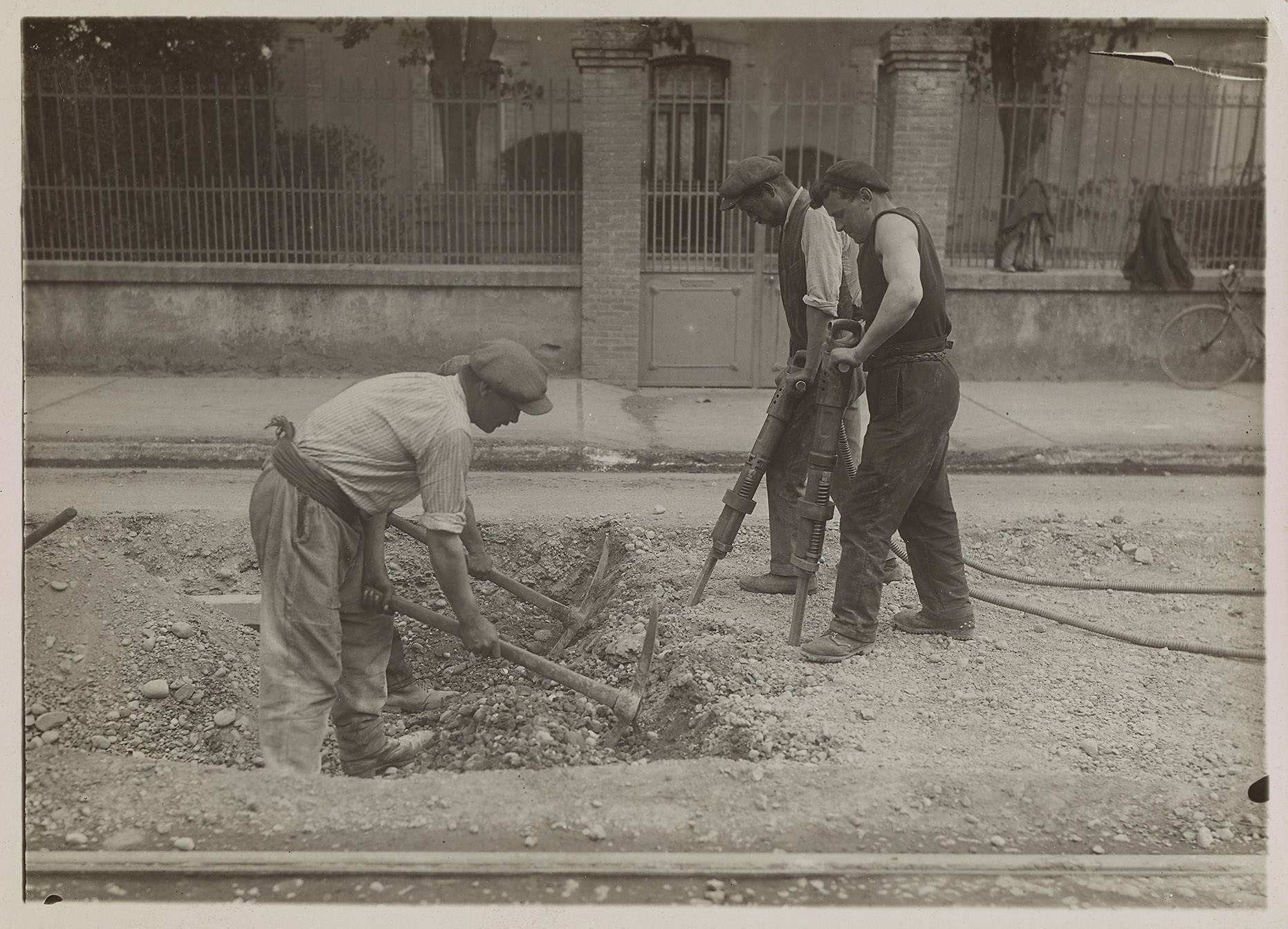

The first part of the twentieth century did not see any major technological innovations in water distribution, and the main projects focused on expanding water supply and distribution networks. However, two important developments occurred after World War I.

In 1918, the Compagnie Générale des Eaux extended its scope of activities by creating Sade, or the Auxiliary Water Distribution Company, to vertically integrate its value chain and directly handle the installation of water pipes. After participating in the war effort, Sade was also involved in the reconstruction of networks in areas affected by the fighting. In 1924, the company integrated Bonna, whose reinforced concrete pipes, invented by Aimé Bonna in 1894, provide an innovative solution compared to the cast iron Chameroy pipes, which are more suitable for gas transportation. Moreover, by utilizing Bonna's pipes, the company was able to avoid the high tariffs imposed by Pont-à-Mousson, its supplier, especially during times of high inflation.

During World War II and onward, the country faced significant new challenges: it had to help rebuild the nation, cope with rapid urbanization, and meet the growing demands for modern comforts from its citizens. As historian Jean-Pierre Goubert pointed out in a 1984 article, “Comfort is still not widespread in the country” in 1946.9

Profound changes in lifestyles were underway, made possible by massive construction projects throughout the country. The iconic representative of this new era was PVC, which, thanks to petroleum chemistry, enabled the production of durable and lightweight pipes for water distribution on an industrial scale by the mid-1960s. The Compagnie Générale des Eaux adopted this new material, which, according to David Colon and Jean Launay, made possible “the water miracle in France.”10

Between 1960 and 1990, two revolutions took place: hundreds of thousands of kilometers of water networks were installed to supply water to households, and tap water finally became widely available in rural areas, paradoxically occurring at a time when France was experiencing a rural exodus. The numbers are impressive: from 1960 to 1980, 475,000 kilometers of network were laid, equivalent to an average of one hundred kilometers per day. This network extended to every corner of the country, facilitating the arrival in households of washing machines, indoor toilets with flush systems, and bathrooms with water heaters. Bathrooms themselves underwent modernization, with architects proposing different types of spaces and designs, ranging from simple shower cabins to large bathrooms resembling personal spas, as highlighted by the Passerelles website of the National Library of France. An illustrative example of this dynamic was the number of subscriptions to the Compagnie Générale des Eaux (CGE), which surpassed 633,000 in 1954 and reached 772,000 in 1958.

Between 1950 and the 1970s, France also erected numerous water towers or elevated reservoirs. These storage facilities, located between treatment plants and end-users, primarily served to pressurize water: the elevated reservoirs utilized gravity to apply the required pressure for supplying water to taps at lower altitudes. Today, there are approximately 16,000 water towers in France. As a result of this frenzy of network construction, from taps to reservoirs, treatment plants, and water towers, by the late 1980s, 99 percent of the French population had access to running water at home, with good pressure, twenty-four hours a day.

© La Pompe de Cornouailles Association

Through the principle of public service delegation and the economic growth in the Trente Glorieuses period, the French government was able to reduce inequalities between major cities and rural areas and promote peri-urban urbanization. Major private companies like CGE have thus accompanied the exceptional development of the Île-de-France region from the 1960s until today. In the northern and eastern parts of Paris, the creation of the Annet-sur-Marne water treatment plant by the Société Française de Distribution d'Eau, a CGE subsidiary in the early 1970s, was intended to supply water to the new town of Marne-la-Vallée and support the urbanization of surrounding suburbs.

However, it is not just about water supply; this development also benefited the socio-economic fabric of the region. Notable milestones in the increasing prosperity of the Île-de-France region included the founding of Charles de Gaulle Airport in 1974, the Paris Nord 2 business park in 1981, and Disneyland Paris in 1992. Another network, the A4 motorway, which gradually took shape during the 1970s, also played a crucial role. Ultimately, the Annet-sur-Marne plant, still operated by Veolia, provided water to 500,000 residents in the northeastern quarter of the region.

According to Eric Issanchou, Technical Director of Veolia's Water activity in Île-de-France, the region's strength lies in the interconnection of networks and production facilities. “We are an interconnected zone that allows, regardless of the operator, the networks to secure each other,” he says. In summary, this situation ensures a secure water supply for the over four million inhabitants served by Veolia and other operators in the region, thanks in large part to the large reservoir lakes constructed upstream of the Seine river basin (the Aube, Marne, Seine, and Pannecière). Today, private companies are no longer responsible for infrastructure investments but can focus on service operation. This is known as a “concession contract.” Historian Konstantinos Chatzis adds, “After World War II, the state intervened heavily to finance the networks. The funds benefited small communities rather than large urban centers. We witnessed a transfer of infrastructure financing.”

In looking back at the foundations of what Veolia has become, it is worth noting that before becoming one of France's industrial flagships, the company was initially a startup, even though no one would have dared to call it that in the nineteenth century. It entered a market where the need was uncertain. It underwent significant strategic and commercial repositioning in its early years. And from the beginning, it had a considerable capital of 150 million francs, which, although reduced later on, allowed it to have a strong financial base from the start and avoid the same fate as the Périer brothers' Compagnie des Eaux de Paris, which remains a small and undeveloped SME.

By investing in water distribution, the Compagnie Générale des Eaux had a major impact on the society that nurtured its growth. One hundred and seventy years after its founding, the water distribution network supplies the average French person with 150 liters every day. France now has 996,000 kilometers of drinking water network, an extraordinary public asset that ensures almost the entire population is served continuously. Today, Veolia provides drinking water to nearly one in three French people.

Thanks to the expertise gained in its country of origin, Veolia now serves more than 111 million people every day worldwide. Cities such as Prague, Budapest, the Pudong district in Shanghai, Shenzhen, Bogota, and Santiago de Chile trust Veolia. Its international presence allows for the rapid improvement of network management skills at a time when challenges remain acute, with aging networks in need of maintenance and renewal and one in three people worldwide still lacking access to safe water, according to the World Health Organization.

Barcelona, a Story of Great Transformation

From Miró to Dalí, from Chagall to Picasso, numerous twentieth-century painters have been inspired by Barcelona. The city is renowned for its architecture, energy, and vibrant colors that ignite the imagination. However, like many European cities, Barcelona would still be an unsanitary cesspool without the arrival of water in the second half of the nineteenth century. Water lies at the heart of the radiance of the Catalan capital.

When evoking the renewal of Barcelona in the late nineteenth century, one first thinks of the Sagrada Familia and Antoni Gaudí. The destruction of the city walls and the Cerdà Plan allowed the city to combine industrial dynamism with urban expansion, facilitating exceptional architectural audacity. This urban development policy, like in many other European cities at the time, also aimed to address public health concerns related to the proliferation of diseases such as cholera.

In 1867, the Barcelona Water Company was established as part of the Cerdà Plan. Just four years later, the water network was operational, featuring an aqueduct, twenty-two viaducts, and forty-seven tunnels, delivering water to Barcelona from the Dosrius river approximately forty kilometers away.

During the 1888 Universal Exhibition in Barcelona, which showcased Catalan modernism and officially marked the beginning of this artistic era, the company, now known as the General Society of Barcelona Waters, presented a fountain comprising water features and lights—now disappeared—in the Ciutadella Park. It also supplied water to the fountain in the famous Plaça Catalunya. These remarkable achievements illustrate the central role of water in the radiance of the Catalan capital.

In the 1920s, the General Society of Barcelona Waters had a distribution network spanning 900 kilometers, covering the entire city of Barcelona and neighboring municipalities such as the Hospitalet de Llobregat, Montcada, and Badalona. It served 44,000 subscribers. The company actively participated in the 1929 International Exhibition, providing the necessary technology and water for the Magic Fountain of Montjuïc.

Three decades later, the company supplied water to 250,000 customers, notably through the opening of the Sant Joan Despí treatment plant, the first major facility of its kind in Catalonia. By the end of the 1960s, the company had nearly one million customers. And at the end of the twentieth century, it contributed to addressing the challenges posed by the population growth Barcelona experienced during the 1992 Olympic Games.

But the history of Aigües de Barcelona extends beyond the city itself. In the 1970s, the Agbar Group was formed in order to diversify, particularly in sanitation, and to share its expertise with other regions, starting with Chile in 1999 through its investment in Aguas Andinas. “Companies must constantly transform and evolve according to the needs of our society, to face the challenges that arise and maintain the trust of customers. This is the story of the Agbar Group, which expanded to share the experience gained in the water sector with other countries, always driven by the same desire to innovate,” explains Ángel Simón, President of Agbar and Director of the Iberian and Latin American zone. In 2005, the company inaugurated its new headquarters, the Agbar Tower, in its birthplace, becoming one of Barcelona's architectural and tourist landmarks.

Since the early 2000s, faced with severe droughts affecting Catalonia, Agbar has developed expertise in water usage efficiency, network effectiveness, and water supply solutions. Agbar has contributed to the development of the El Prat desalination plant, the largest in Europe. The company has also demonstrated its capacity for innovation in the recovery and reuse of wastewater, which has advanced since the implementation of the reverse osmosis treatment line at the Baix Llobregat wastewater treatment plant.

Recovered water now represents 25 percent of the water resources used for supplying the metropolitan area of Barcelona for industrial, agricultural, and urban purposes, such as street cleaning and watering green spaces.

The integration of Agbar into Veolia in 2022, along with most of the international activities previously held by Suez, provided an opportunity to accelerate the sharing of expertise worldwide, reaching even Northern Catalonia in France, in Saint-Cyprien. The mobilization of Catalan ultrafiltration expertise has made it possible to consider producing recycled water that can replace water from the water-deficient Villeneuve-de-la-Raho lake.

Investing in Ecological Transformation: A Lesson “Made in Marseille”

In 1834, Marseille was devastated by a cholera epidemic that claimed over three thousand lives. The municipal team in place decided to address the identified culprit head-on: the city's unsanitary conditions and inadequate water supply, which amounted to no more than one liter per person per day. To tackle this issue, they embarked on the construction of the Marseille Canal to bring abundant water from the Durance River to the Phocaean city.

It was a political priority, with Mayor Maximin-Dominique Consolat determined to carry out the project “whatever happens, whatever the cost.” The means were indeed found, and the canal was inaugurated in 1854. The annual construction works represented a budget equivalent to that of the entire municipality for fifteen years.

This figure is interesting to put into perspective. In their 2023 report on financing the climate transition in France, Jean Pisani-Ferry and Selma Mahfouz mention the need for France to mobilize 34 billion euros of public spending over seven years to achieve the target of a 55 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. That represents, relative to the 1,500 billion euros of annual public spending, only 2.2 percent over a period half as long—in other words, nearly one hundred times less effort than what Marseille undertook for the construction of the canal. This serves as a reminder that the investments required to guarantee ecological transformation are entirely realistic in light of history, provided there is collective will.

Between Industrial Revolution and Thermal Water: The Fascinating Story of Le Touquet-Paris-Plage

What connects the daily newspaper Le Figaro, the Prince of Wales, Veolia, and the rise of nineteenth-century railways? It's Le Touquet! Behind this peaceful seaside resort lies a remarkable gamble: transforming a hamlet on the Opal Coast into a beach resort that would rival Cannes or Biarritz.

Le Touquet-Paris-Plage, a legendary seaside resort located on the northern coast of France, embodies the perfect blend of elegance and history. In the nineteenth century, a Parisian notary named Alphonse Daloz acquired the Domaine du Touquet, a hamlet mainly composed of sand, with the intention of transforming it into a vast pine forest. His plan quickly changed when Hippolyte de Villemessant, the founder of Le Figaro, suggested developing it into an exclusive resort for Parisians. Thus, in 1882, Paris-Plage was born. Within just one year, it had attracted around thirty residents.

Two British men, John Whitley and Allen Stoneham, captivated by the untapped potential of this charming coastal region, set out to turn this dream into reality. Their adventure began when they acquired untouched lands north of the Canche estuary. Their ambition was to transform the village into a luxury seaside resort. Water played a crucial role at the heart of this audacious venture, as there was initially little infrastructure—not even running water.

Firstly, a robust water distribution system was established, even before it was implemented in major French cities. An outbreak of typhus in 1898 raised suspicions of well contamination, as these wells provided water to the villas and for sanitation purposes, which accelerated the deployment of the water system.

In 1904, realizing that the initial water resources would be insufficient to supply the expanding region of Le Touquet, the family-owned company Eaux de Berck-sur-Mer drilled a fifty-meter-deep well in the Rombly area, which was previously a flooded zone. This pumping station, known simply as “Rombly,” had a remarkable feature. Its water, renowned for its therapeutic qualities due to low nitrate levels, could be used without any chemical treatment. Recommended for liver and kidney disorders, the water was even sold in bottles. Its reputation was such that a pavilion was built in the garden alongside the castle park, allowing visitors to taste the water, further enhancing the station's reputation.

The development of the seaside resort gradually transformed a tranquil expanse of dunes into a bustling tourist destination. The choice of the name “Le Touquet-Paris-Plage”' was not a coincidence. By associating the name of the French capital with the seaside resort, Whitley and Stoneham aimed to attract the attention of the Parisian aristocracy, who were always eager for exclusivity. Everything was done to encourage them, with the Nord railway and the Étaples-Paris-Plage electric tramway line, inaugurated in 1900, allowing city dwellers to reach the seaside in just three hours. Le Touquet-Paris-Plage became an ideal destination for urbanites seeking relaxation and entertainment.

By the early twentieth century, success had been achieved. The British high society in particular flocked to this haven of peace, rivaling the most prestigious European tourist destinations. Prominent personalities, artists, and renowned writers such as the Prince of Wales, Edward VIII, and Noël Coward succumbed to the charms of this seaside resort.

The First World War brought new challenges, however. Devastating battles had a major impact on the region, destroying a significant part of the resort's infrastructure. However, the colossal post-war reconstruction effort allowed Le Touquet-Paris-Plage to survive these hardships and restore its former splendor. The Compagnie générale des eaux (CGE), despite facing its own challenges, invested in the area: “It was after 1914 that the first concessions were acquired in various neighborhoods of Le Touquet,” recalls Jean-Claude Douvry, former CEO of Sade, who was responsible for operating the network at one point. “This period, marked by rising energy costs and inflation, posed challenges for water distribution companies.” This ability to seize crises as opportunities for growth became a constant factor in the company’s growth.

Until the conclusion of World War II, the independent Société des Eaux du Touquet distributed gas and electricity along with water. However, after the nationalizations that followed the war, CGE focused exclusively on water supply. With the advent of modern comforts, the increasing demand for water far exceeded the capacities of the Rombly station, especially during the summer periods in Le Touquet-Paris-Plage and its surroundings. To tackle this new chapter on the Opal Coast, a comprehensive reinforcement program was launched.

In 1989, CGE acquired Société des Eaux du Touquet, demonstrating that its development involved resilience in the face of fragile local companies and sometimes even picturesque acquisitions: “The company was acquired from its owner Daniel Vinay through a developer working with Bernard Forterre, who happened to know Madame Vinay's first husband. It was not without difficulties, as the religious society of Father Halluin, on the other hand, was not willing to sell,” recalls Jean-Claude Douvry. One of the company's notable achievements was, in the early 1990s, “redirecting the route of the A16 motorway” away from areas that could have posed pollution risks to the Rombly source.

Today, Le Touquet-Paris-Plage continues to draw visitors from around the world. This historic seaside resort has preserved its unique charm by cultivating an intimate relationship with water, a source of life and renown for this rare gem on the Opal Coast.

- In an artesian well, water naturally gushes out of the ground. The trick lies in “connecting” to a vein that feeds a pressurized groundwater table and utilizing the power of the water to bring it out through the well. ↩︎

- A highly influential reformist movement in the nineteenth century that advocated for a complete reorganization of society. Saint-Simonism “laid the foundations of an industrial utopia” in opposition to the social order of the Ancien Régime. It constructed the happiness of humanity on the progress of industry and science, according to the Gallica blog of the National Library of France. ↩︎

- BRAUDEL, Fernand. The Identity of France: History and Environment. London: Collins, 1988. ↩︎

- GMELINE Patrick de, Compagnie générale des eaux : 1853-1959, De Napoléon III à la Ve République. Paris : Ed. de Venise, 2006. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- PEZON Christelle. Le service d’eau potable en France de 1850 à 1995. Paris : CNAM, CEREM Paris, 2000. ↩︎

- GOUBERT, Jean- Pierre. « La France s’équipe. Les réseaux d’eau et d’assainissement. 1850-1950 ». Les Annales de la recherche urbaine, no. 23-24 (1984). ↩︎

- COLON, David, LAUNAY Jean. L’eau en France, entre facture et fractures ! Paris: Nuvis, 2017. ↩︎