Inventing Waste: From a Waste-free Society to Disposable Everything

The rise of private waste collection and disposal sectors marks a major anthropological shift in all industrialized countries from the late nineteenth century onwards. Previously, human products were constantly reused, but during the 1800s they began to be discarded in massive quantities, becoming what we now know as waste—in vast quantities that needed to be collected and removed from sight of those who produced them. The idyllic vision of a pre-waste world must be nuanced with the older term of “ordure,” which signifies the combination of bodily fluids and excrement that contaminate but also constitute the essence of territorial ownership, according to philosopher Michel Serres. Waste emerged when refuse was no longer seen as a resource integrated into the grand cycle of the urban metabolism—albeit something that collected in European streets in a manner that would be intolerable today. In eighteenth-century Rouen, for instance, the auction system allowed for the collection of barely three hundred grams of waste per day per inhabitant, while Paris, Europe's second-largest city in 1780, was inundated by a black, nauseating sludge that stained clothes. This sludge was a mixture of construction site residue, incineration byproducts from chimneys, and leaks from cesspools. Collected at the foot of the Île de la Cité and Notre Dame, it was dumped into muddy streets integrated into the urban fabric, alongside Les Invalides and the École Militaire, contributing to the city's pestilence. This was accompanied by the smoke from cooking tripe, the stench of suet melters, the putridity of stagnant water used by laundresses, and the miasma from tanneries and slaughterhouses.

Grégory Quenet

Were waste and garbage invented? This is the thesis brilliantly defended by urban planning researcher and teacher Sabine Barles in her book, The Invention of Urban Waste: France, 1790–1970.1 The author refers to “urban” waste, and the adjective is crucial. The meaning of “waste” depends on how it is understood, as definitions of this term, as well as other words used throughout history to describe the byproducts of human activity (such as sludge, refuse, filth, residues, and sewage) have reflected different visions, eras, and ways of life. According to Christian Duquennoi, an engineer at the École des Ponts and researcher at Irstea (National Research Institute of Science and Technology for the Environment and Agriculture), the concept of waste refers to “matter that no longer has utility or function, but it does not exist in absolute terms.”

In his book, Waste: From the Big Bang to the Present Day,2 he traces the origin of this concept back hundreds of millions of years after the Big Bang and the creation of the universe when planetary systems formed and expelled “waste,” which consisted of matter and energy that were not useful for the functioning of these stars. Within Earth's ecosystems, the undesirable products expelled by living organisms are not lost to everyone. The waste from some organisms becomes food for others, as exemplified by the carbon dioxide we exhale, which promotes plant growth through photosynthesis.

“This is the beginning of the circular economy!” notes Christian Duquennoi mischievously. In a more prosaic sense, the French word “déchet” comes from “déchoir,” which describes what falls to the ground during human activity: wood chips produced from tree trimming, pieces of fabric that fall after use, excrement returning to the earth, etc. Waste serves as the raw material for archaeologists, who work with what was considered useless by preliterate societies. However, for most of human history, most byproducts were reused. It was only in the twentieth century that Antoine Compagnon, a member of the Académie française and author of The Ragpickers of Paris, identified this period as a “parenthesis” in history—a time of disposability and widespread waste. It was during this period that solutions had to be found to transport and manage the countless amounts of waste now being produced.

The Nineteenth Century: The Valorization of Waste as a Necessity

During the Middle Ages and the Ancien Régime, historians and archaeologists have relatively well-documented waste management practices. From the moment of sedentarization, agriculture, and animal husbandry, it can be observed that waste began to be expelled from homes—as Yuval Noah Harari teaches us in Sapiens, dogs, “man's best friend,” were originally wolves that came to the outskirts of villages to feed on garbage before being domesticated by humans. However, as Marc Conesa and Nicolas Poirier, teachers and researchers in the humanities, note, these waste materials “pursued another career.”3

During this era, almost nothing was lost; everything was transformed. Animal excrement provided fertilizer for market gardeners, all meat was consumed, skin was used to make leather, fat was reused for soap and lighting, and crushed bones were reused as glue in proto-industrial applications. According to Marc Conesa, waste management and its associated nuisances were concerns for certain communities, but population growth and the need for fertilizer found an outlet in the fields, to the extent that “waste management shaped agrarian structures and territories.” The nineteenth century merely gave quasi-industrial dimensions to ancient waste recovery activities due to increased demand and technological advancements. Modern societies discovered virtues in waste while simultaneously finding it repugnant for hygienic reasons. According to Sabine Barles, who employs the concept of “urban metabolism” in her book, the city, industry, and agriculture smoothed out the exchange of materials in the nineteenth century in order to valorize them. In summary, “the circulation of materials from homes to streets, from cesspits to factories or fields contributed to the initial rise of urban consumption. Scientists, industrialists, and farmers viewed the city as a mine of raw materials and, alongside municipal administrations, technical services, and ragpickers, worked toward an urban project aimed at leaving nothing to waste.”

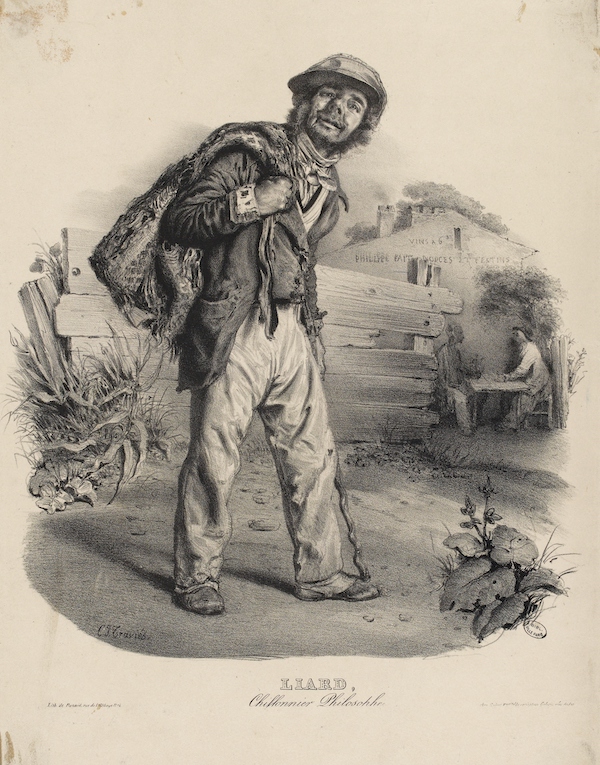

The symbolic embodiment of this vision is the ragpicker—including the female ragpicker, who, to do her justice, represented a third of the Parisian ragpicking workforce.4 As a well-known figure of the nineteenth century, they were depicted in engravings by Daumier, Gavarni, and Traviès and in an allegory of the poet for Baudelaire. The ragpicker was also described by Frédéric Le Play in a detailed chapter of his sociological study on workers,5 where he outlined the budget of an exemplary ragpicker. Antoine Compagnon reminds us that “they called themselves ‘small industrialists.’ They were independent workers, like today's self-employed entrepreneurs. They said they didn't want bosses, but this independence was often linked to alcoholism, which prevented them from having regular employment. However, there are cases of ragpickers who became paper manufacturers and made a fortune.”

If ragpickers were able to make a living from their work, it is because the demand for rags had exploded across Europe to the extent that their exportation was prohibited in France from 1771 onwards. Rags were used to make paper, which saw increasing use throughout the eighteenth century. The rise of the press, the printing boom, and the democratization of education led to a significant increase in paper production, from 18,000 tons in 1812 to 350,000 tons in 1900. It required 1.5 kilograms of rags to produce 1 kilogram of paper, making up half of the manufacturing cost. There was even a rag market with prices varying depending on quality, often unrelated to the original material's price, whether it be cotton, hemp, or linen. (Wool rags were not used for paper production but rather for making new clothing.) Ragpickers sorted everything they collected, including bones (they were called “rag and bone men” in England), which would be turned into buttons or phosphorus for matches. They would then sell their cargo to wholesalers, known as “master ragpickers,” most of whom were located on the Rue Mouffetard in Paris. These ragpickers served as agents of order, possessing knowledge about the neighborhood through their work and providing information to the police. They had a mysterious presence, wandering the streets at night with hooks and sacks full of rags, sometimes intoxicated and always dirty. Ragpickers were registered at the prefecture of police and awarded “chiffon medals,” although there were many undocumented clandestine ragpickers. Their numbers dramatically increased during the nineteenth century, reaching 200,000 in the Seine department in 1884, according to the Chamber of the Ragpickers' Syndicate!

The vidangeur was the counterpart of the ragpicker, responsible for another significant recovery activity of the time: the collection of vidanges, or excrement dumped into cesspits and later moved to open-air dumps. With a 40 percent population growth throughout the eighteenth century, France became a demographic giant. Agricultural areas expanded, leading to a veritable “hunt for fertilizers,” as noted by Sabine Barles. The demand was so high that farmers and entrepreneurs were willing to pay for the right to transport urban excrement to rural areas. This was exemplified by Bridet, a Norman farmer who, in 1787, purchased the right to exploit the famous Montfaucon dumpsite in Paris6, now the location of Parc des Buttes-Chaumont. He patented a process to transform the fecal matter into dried poudrette, serving as natural fertilizer for farmers. New patents emerged throughout the nineteenth century, resulting in numerous poudrette factories that supplied suburban cities and rural villages until the twentieth century. However, criticism grew regarding the quality of this human-origin fertilizer.

To these sources of fertilizer, one must also add “urban sludge,” which consisted of household waste dumped in the streets mixed with sand, soil, and various other materials (including horse excrement, with Paris having eighty thousand horses in 1900). At one point, urban sludge was directly collected by servants sent by farmers, who provided them with horses, carts, and tools; it then became a competitive market among resellers. For large cities like Paris, the interest in sludge valorization was also driven by hygiene concerns, as those who wanted to sell it had to clean it from the streets.

The End of a Circular World: The Development of Chemistry and Hygiene

This circular process, in which the countryside fed the urban population, which, in turn, produced fertilizers for the fields and raw materials for industry, reached its peak around 1870. Several significant events gradually put an end to it over the next sixty years. “At the end of the nineteenth century,” analyzes Christian Duquennoi, “the cost of primary and secondary materials became so prohibitive that an innovation race was launched to replace them with new raw materials. In a way, the invention of paper pulp, which used wood fibers instead of rags, was the first domino that set off all the others.” (This led Antoine Compagnon to suggest that “the era of the ragpicker coincided with the field of chemistry lagging behind the first industrial revolution.”)7. Petrochemical materials, such as celluloid and plastic, replaced bone and horn in the production of jewelry, boxes, and games. Bakelite, invented in 1909 by Leo Baekeland, was the first plastic resin to substitute for ivory, used to make billiard balls, as well as toys, radios, automobile parts, pens, lamps, ashtrays, and coffee grinders. In 1913, the Haber-Bosch process made it possible to invent chemical fertilizers by fixing atmospheric nitrogen. For economic and hygienic reasons, these chemical fertilizers soon became preferred over sludges and excrements due to their higher quality and lower toxicity. “The guano from Peru, the nitrates from Chile, and even more so, chemical fertilizers worked against the use of human fertilizer,” confirms Alain Corbin in The Foul and the Fragrant.

The development of chemistry accompanied an increasing sensitivity to odors, to which ragpickers initially provided a response. The emergence of the bourgeoisie, which preferred modesty over the exuberance of the aristocracy, advocated for milder scents. The advent of individualism and a strong state contributed to the privatization of waste. All of these phenomena led to a greater emphasis on hygiene, overshadowing utilitarian considerations, despite their significance. “More than ever, ‘disinfecting’—and thus deodorizing—is part of a utopian project: one that aims to seal the testimonies of organic time, to repress all irrefutable markers of duration, these prophecies of death that are excrement, menstrual products, carrion decay, and the stench of the corpse. Olfactory silence not only disarms the miasma, but it denies the flow of life and the succession of beings; it helps bear the anxiety of death.”8

Later on, hygiene often served as a pretext or justification for the development, made possible by industry, of disposable products, as philosopher Jeanne Guien eloquently recounts in her book Consumerism Through Its Objects: Display Cases, Disposable Cups, Deodorants, Smartphones...9 The author cites the prohibition of tin cups, available at public fountains in the early twentieth century in the United States. Out of concern for germs, public policy-makers launched prevention campaigns and replaced the tin cups with single-use cups made from paper coated with paraffin, which were replaced with single-use cups made of paper lined with paraffin, then cardboard and plastic, which saw the global success that we know today. Another famous example is the creation of disposable tissues, the famous Kleenex©, by the company Kimberly-Clark in 1924. Initially, they were invented to dispose of surplus cellulose fibers used for bandages during World War I and were initially intended for removing excess makeup cream before gradually transforming into tissues. While doctors had already recommended the use of disposable fabrics for hygiene reasons in the nineteenth century, it was only afterwards that the company used this argument to sell its product. With the massive democratization of consumption, “waste began to be equated with abandonment,” as explained by sociologist Baptiste Monsaingeon in an interview for the podcast Metabolism of Cities.

To accompany this evolution, public hygiene policies were also implemented, with the most notable symbol being the generalization of the trash can, made mandatory in Paris through a decree on November 24, 1883. Symbolically, it is important to note that Prefect Eugène Poubelle had initially hoped for sorting by residents, encouraging them to throw sharp waste (glass, oyster shells) into one box and household waste into another. These garbage boxes were calibrated and designed to be easily emptied into collection carts at regular intervals, while caretakers had the heavy responsibility of taking them out and keeping them clean.

One might imagine that the population at the time, tired of living surrounded by garbage, would be relieved or even unanimously support this reform. However, the opposite was true. The decision was met with fierce criticism from opponents and constant mockery in the satirical press. In an engaging article titled “Eugène Poubelle put into a box!” historian and curator Agnès Sandras reveals the surprising content of these controversies. Firstly, Poubelle, the Prefect of the Seine, was accused of negotiating with garbage bin manufacturers behind the scenes, thus appropriating citizens' waste without compensation. Another criticism, which may seem surprising, was the measure's egalitarian nature: due to the trash cans, both wealthy bourgeoisie and domestic workers would find their food scraps in the building's courtyard!

Eugène Poubelle, The Prefect10 Who Aimed to Clean Up Paris

As the inventor of the trash can and a pioneer of selective sorting, Eugène Poubelle, prefect of Seine, revolutionized hygiene in Paris and in France. But how did the surname “Poubelle” become the accepted French word for a garbage bin?

Eugène Poubelle was born in Caen, 1831, into a bourgeois family. After studying law and obtaining a doctorate, Poubelle began his career as an academic. It wasn't until the age of forty that this distinguished professor took on administrative duties when Adolphe Thiers, the president of the Third Republic, appointed him as prefect of Charente in 1871. From 1871 to 1883, Eugène Poubelle served in various prefectures in France, including Isère, Corsica, and even Bouches-du-Rhône.

In 1883, Eugène Poubelle settled in Paris and became the prefect of Seine, a position that was more or less equivalent to that of the mayor of the capital—a role previously occupied by Baron Haussmann about thirty years earlier.

Convinced by hygienist ideas, Poubelle, who took office in October, issued an order in November (the 24th, to be precise) that organized waste collection in Paris. This measure revolutionized the daily lives of Parisians.

The order required property owners to provide their tenants with “wooden containers lined with tin” and equipped with a lid, for collecting waste. These containers were then placed in the street by each building’s concierge, for collection. But that's not all—Prefect Poubelle also envisioned the beginnings of selective sorting: an additional box was provided for papers and rags, while a third box was designated for broken crockery, glass, and oyster shells.

Both Parisians and the media reacted strongly against these changes. The Petit Parisien newspaper's headline on January 10, 1884, read, “You'll see that one of these days, the prefect of Seine will force us to bring our garbage to his office.”

On January 15, 1884, the measure was implemented, and Prefect Poubelle was accused of trying to eliminate ragpickers, who would see a decline in their activities. On January 16, an article in Le Figaro mentioned for the first time the “Poubelle boxes,” which would later become commonly known as poubelles (trash cans) in everyday language. In fact, the word “poubelle” appeared in the Grand Dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle (The Great Universal Dictionary of the 19th Century) as early as 1890. It was listed a few pages after the term Haussmannien (referring to Baron Haussmann's urban renovation), and unfortunately, it acquired a less praiseworthy connotation.

In his hygienist efforts, Eugène Poubelle went beyond waste collection—he was also responsible for the first ordinances imposing sewer systems.

The prefect eventually left Paris in 1896 to work at the Vatican, where he was appointed as the ambassador of France. However, he ended his career in the Aude department, serving as a county councilor until 1904. Eugène Poubelle died on July 15, 1907, at his Paris residence. Today, there is a street named after him in the 16th arrondissement of Paris. It is the smallest street in the capital, having only one address. Convenient for collecting trash!

In the Journal amusant, a short story portrays a bourgeois couple and their maid sorting through waste:

“The Maid: Should the bone from the leg of lamb go with the oyster shells?

Mr. Bellavoine: Obviously, it is unsuitable for agriculture.

Mrs. Bellavoine: Personally, I would put it with the household waste; it can be used for animal charcoal.

Mr. Bellavoine: To refine sugar. It doesn't promote growth in the fields.

The Maid: Drat! I'll just stick it in the middle... and what about Madame's old pouf?

Mrs. Bellavoine: On the rags... They are foolish with their waste classification: there should be as many containers as there are categories of objects.”

Furthermore, the press was concerned about the fate of the ragpickers: what would become of them now that they could no longer rummage through the garbage, all piled up and locked in a box? In the trash can, all the waste got mixed up, and its quality deteriorated. Faced with the protests of the ragpickers and their allies, Eugène Poubelle relaxed the regulations and allowed them to sort the waste on a white sheet before the cart passed by. Nevertheless, the birth of the trash can marks the end of the ragpickers' reign: “They were gradually driven out of the fortifications of Paris, toward the outskirts,” recounts academician Antoine Compagnon, “because they were less needed. They then began using not a basket but a cart and collected almost anything. Scrap metal dealers took over, as scrap metal is still profitable for recycling today.” According to Sabine Barles, it is in the 1930s that society definitively abandoned this waste valorization: incineration was too costly, spreading fields required too much space and water, and ragpicking raised too many hygiene concerns. The development of small collection enterprises and the transition to automobiles and compacting bins that compressed waste eventually made any ragpicking activity virtually impossible, making way for increasingly professionalized waste collection, albeit still a profession that was socially stigmatized.

The first collection and cleaning companies: Transportation in the service of cleanliness

Initially, street cleaning and sludge removal were entrusted to multiple small family-owned companies. Unlike water services, waste management did not initially require significant capital or technical, commercial, or contractual expertise of the sort which led to the emergence of a Compagnie générale des eaux (CGE). These companies partially earned their income by selling valuable waste. However, as the cost of cleaning increased due to urban growth and the value of sludge and rags decreased, these companies had to regularly renegotiate their contracts with the cities. Some obtained long-lasting concessions, constantly renewed, and grew accordingly, such as the Grandjouan company in Nantes, which cleaned the city's streets and transported waste from 1867 to 1947. Founded by François Grandjouan and his family, the company had fifty carts, eighty horses, sixty drivers, and one hundred sweepers to carry out its tasks.

In Nantes, as well as in Paris and Lyon, the authorities wanted to encourage residents to participate in keeping the city clean by introducing a “cleaning bucket” designed to collect garbage, which became known as the sarradine, named after Émile Sarradin, a perfumer who proposed the creation of a municipal sweeping tax. This was in 1878, and the Grandjouan company faced an enormous workload: removing mud, garbage, excrement, dust, ashes, broken glass, weeds, tree leaves, and scattered stones from the streets, as well as sweeping squares, quays, stairs, promenades, and doing daily cleaning of market halls. They even captured stray dogs. Tombeliers (cart drivers), ragpickers, and sweepers worked in terrible hygiene conditions, using shovels, rakes, and picks to collect and deposit waste into the carts. The buckets had to be carried up on ladders and then emptied, a particularly exhausting task.

The need to improve these conditions led these small, local waste collection and storage businesses to turn to the mechanization of transportation and the improvement of bins and carts. To achieve this, they sometimes joined forces with other companies that ventured into automobile manufacturing. However, the transition from horse-drawn carts to automobiles was very slow. Although the first front-wheel-drive and front-wheel-steering carts were developed by the brilliant inventor Georges Latil as early as 1897, it was not until the 1920s that horses were truly replaced by automobiles, especially for hygiene reasons, as animal excrement was now considered a nuisance. Georges Latil eventually found an inspired buyer for his innovative front-wheel drive in a young graduate of the École Polytechnique, Charles Blum. Blum saw the automobile as the industry of the future and invested the significant sum of 1,200,000 francs in the company.

In 1912, the two men founded the General Automobile Enterprise Company (CGEA). The First World War quickly confirmed the performance of Latil tractors, which contributed to the national mobilization, functioning on rough terrain with four-wheel steering and drive. After the war, CGEA provided traction vehicles to many municipalities that wanted to use them for street cleaning, particularly in certain neighborhoods of Paris. To expand the company, Charles Blum chose to acquire small transport companies in provincial areas, such as Maison Robert Vallée in Caen and Maison Jean et Beuchère in Rennes, which enabled CGEA to obtain contracts for household waste collection in these cities in 1930 and 1934. Although the Grandjouan family in Nantes resisted abandoning their horses for a long time, they eventually succumbed to the gradual relocation of landfills and fertilizer delivery points, since horse-drawn carts could not travel more than eight kilometers. In contrast, tractors could venture up to twenty-five kilometers. Convinced, the Grandjouans added a transportation service to their street-cleaning business.

The figure of the ragpicker, often a local presence, gradually gave way to that of the road worker or garbage collector, clinging to the back of their garbage truck. They began working very early in the morning and carrying the waste farther away, as people no longer wanted to live near garbage dumps. The issue with waste was no longer finding a new use for it, but burying or disposing of it in rivers via sewage systems. Those who managed the waste worked difficult jobs that were often the objects of disdain, but they allowed city dwellers to live in clean cities. Today, both companies, Grandjouan and CGEA, are part of Veolia's history. “For decades, local authorities ‘made do’ with solutions for waste collection and disposal,” explains Franck Pilard, Veolia's Commercial Director for Local Authorities in Waste Recycling and Valorization. “Some municipalities had waste evacuated by a small local actor—the mayor's brother or a family farmer—sometimes until the 1960s. They were family businesses with a long history that were acquired by CGEA when they needed to scale up due to demographic, urbanization, and household consumption pressures.”

Thus, Veolia's waste collection and valorization activity has two origins. One is through organic, biological development, “which grows gradually,” to use the words of Paul-Louis Girardot, former CEO and administrator of the group. As early as the 1960s, CGE developed waste collection activities, such as in Saint-Omer, where the municipality realized that “it was not working well” and that those responsible for waste collection were “not very reliable” and needed help. The other origin is through acquisitions. In 1980, CGEA was fully integrated into the Compagnie Générale des Eaux, which was already a shareholder of the company, to consolidate a coherent range of service offerings: water, sanitation, waste, and Cleanliness. In addressing both municipalities and industrial clients, Veolia acquired companies such as Ipodec, “whose original name, ‘Ordures usines’ or ‘Factory Refuse,’ left no doubt about its core business!” recalls Didier Courboillet, Deputy CEO of Veolia's Waste Recycling and Valorization activity. This activity was briefly known as Onyx until the creation of the Veolia brand.

FROM RAGPICKER TO SOCIAL OBSERVER: THE FIGURE OF THE GARBAGE COLLECTOR IN HISTORY

“‘Garbage collector,’ that's the 1970s, it's over. Now, in 2021, it's a ‘refuse collector,’ you know!” In the words of Jimmy, a young TikToker who works as a cleaner in his city and built a reputation on social media during the Covid pandemic, the semantic shift reflects the need for recognition in a profession that has not changed much in seventy years. Certainly, the days when road workers, ragpickers, and carters worked in appalling conditions between the late nineteenth century and the 1930s are long gone. From morning till night, they toiled with great difficulty to clean impassable and hard-to-reach streets, to carry heavy metal bins up makeshift ladders and dump them into the truck, and sometimes to sift through them for initial sorting. However, the hardship of the work remains a historical constant for a profession confronted with the risks associated with proximity to waste and road traffic. The French word for “garbage collector,” éboueur, comes from the word boues, which, as early as the Middle Ages, referred to the mixture of household waste, soil, sand, animal excrement, and other residues that accumulated on the streets of large cities, particularly in the central gutter designed to remove them with the rain.

At that time, the boueux or boueurs—of which éboueur is a euphemism—or the gadouilleurs represented the last link in the garbage recovery chain. Although the transformation of this mud into manure gave it increasing value, this work was an object of disdain throughout the nineteenth century, and it was the least fortunate ragpickers or farm servants who took care of it. With the invention of the garbage can and the proliferation of waste in the twentieth century, the profession evolved: in large cities, private companies, such as CGEA and SITA in Paris or Grandjouan in Nantes, sometimes joined municipal authorities to systematically collect garbage. The figures of the sanitation workers began to resemble what we know today: a truck driver, two loaders at the back, called “garbage collectors” or “refuse collectors,” and one or two street sweepers, often women at that time. In the 1920s–1930s, the ragpicker on the cart, who participated in the rounds for the purpose of sorting, was replaced by a municipal road worker. In 1936, during the Popular Front, garbage collectors went on strike en masse and obtained their first social benefits. Employees working for private companies eventually, after a long struggle, obtained the same rights as municipal employees.

Mechanization also improved their working conditions, and compacting bins saved them time, but the profession in cities would not change much for decades. In rural areas, collection was more artisanal and rustic, both in terms of equipment and organization. Garbage was collected by ragpickers, scrap dealers, all kinds of recyclers, and local farmers using a cart and horses, or occasionally a tractor. It would take until at least the 1970s to see the modern system being implemented everywhere, following the model of major cities like Paris, Lyon, or Nantes.

During the “Trente Glorieuses” (the thirty years of economic prosperity following World War II), the profession began to gain better recognition, although this recognition remained very ambivalent. On the one hand, garbage collectors were appreciated for cleaning cities where waste proliferated, but on the other hand, few wanted to see their children pursue this career. “If you don't work hard at school, you'll end up at Grandjouan!” was the threat in Nantes and its region, recalls Franck Pilard, RVD Sales Director at Veolia. Nevertheless, the garbage collector was part of the life of a neighborhood or village and even evoked nostalgic childhood memories for some. In 1969, the famous cartoonist Marcel Gotlib portrayed “the garbage collector of [his] childhood” in a comic strip from the Rubrique-à-brac series, using laudatory terms without a hint of derision: “Yes, it was him, clinging to the side of his machine, like Apollo on his chariot, radiating in the rising sun.” Young Gotlib watched the garbage collector go about his rounds and leave, “taking with him a scent of mystery and adventure,” until one day he succeeded in meeting him and being initiated into the joys of garbage collection. Antoine Compagnon, author of the book Les chiffonniers de Paris, regrets that they are seen less often:

“When I was a child in Paris, we saw them during the day; they collected garbage between 7 a.m. and 8 a.m. Their current discretion is also linked to the transformation of large cities, because neighborhoods at the time had retained a sense of community that has now been lost, along with small businesses.” In rural areas and small towns, this proximity has not been lost. Researcher and teacher Marc Conesa lives in a village in the Pyrénées-Orientales where garbage collectors still play the role of social observers: “They create a presence at specific times. In the morning, we see them at the bakery before or after the collection, checking that everything is fine, that the grandmother has taken out her trash, that the dog is not on the road, etc. They are actors who have a good knowledge of the area; they know the schedules of residents and shopkeepers, and they are the ones who find lost, sick, or intoxicated people in the street.” Our new relationship with waste, partly through sorting, recycling, and valorization, but also growing out of times of crisis, reveals their importance in the eyes of the population. During the Covid pandemic, for example, garbage collectors were applauded and received letters of congratulations, but the strikes in 2023 were supported to varying degrees by the French, with 57 percent of them wishing for the requisitioning of employees.

Today, the garbage or refuse collector is essential for maintaining clean cities. If society wants to meet the challenge of waste reduction, this profession will need to evolve in the future. According to Franck Pilard from Veolia, “we need to reduce the frequency of household waste collection and decrease the size of bins to encourage citizens toward more responsible consumption. This implies involving more people in the subject of reuse, repair, and supporting our employees even more to become ambassadors of recycling.”

“We are the originators of collectors, from ironmongers to cardboard collectors,” confirms Martial Gabillard, Director of Flow Valorization at Veolia, proud of this legacy and the concrete and meticulous mindset that has endured over time. Today, echoing the ragpickers of the past, this former regional director in Rennes mentions papermakers: “We do everything for them: we manage their sludge and bring them paper for recycling. We take care of their supplies, energy provision through sludge, and water treatment. In short, we support them in the major challenges of their profession.” Between the past and the present, the sanitation industry now finds in waste the notions of flow, value, and circularity, albeit while managing unprecedented quantities and types of waste.

“Collection wasn't so complicated,” says Franck Pilard. “It was mainly about evacuation for hygienic purposes, so municipalities could handle it. However, waste treatment always required more in-depth skills and investment, which is why municipalities now delegate more to private companies. Our strength lies in the public service delegation model, which allows Veolia to leave a mark through this approach that has spread worldwide.” In the twentieth century, the age of recovery gradually gave way to the era of waste treatment. At that time, the focus came to be on transporting waste far away for incineration or landfill, but carried out industrially. “‘Cover this waste that I cannot see’ could be the motto of the time. The cities' hygienic concerns prevailed above all else, long before ecological considerations questioned this model.”

In London, cleanliness is a top priority for the iconic Westminster district

Big Ben, the Palace of Westminster (seat of the British government), Buckingham Palace (seat of the British monarchy), Tate Britain, St. James's Park, Victoria Station...all these iconic places are located in one prestigious district in the heart of London: Westminster. And this political and tourist center of the United Kingdom is given special attention.

To meet the expectations of the millions of people who pass through this iconic district every day, Veolia has been ensuring its cleanliness twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week since 1995. Every week, 200,000 tons of waste are processed and 8,400 kilometers of streets are swept. Busy arteries, such as Oxford Street and the surroundings of Piccadilly Circus, are swept two or three times a day and at night to ensure compliance with the strictest cleanliness standards.

This London district is the venue for numerous annual events such as the London Marathon, the Notting Hill Carnival, the annual Pride march, and of course, major royal events such as jubilee celebrations, weddings, coronations, and funerals. Therefore, in addition to the daily maintenance required in Westminster, Veolia's teams are on hand to provide top-quality cleaning services during these large gatherings. One can see electric waste collection vehicles busy about the streets of Westminster, which are recharged with green electricity produced in the waste treatment plant serving the district's residents: a closed loop! To further enhance the cleaning service, Veolia is partnering with Westminster to make it a “zero-emission” local authority by 2030, through an electrified fleet and innovative collection methods.

These services are always encouraged to improve, with a performance-based market that remunerates the operator based on the achievement of goals set in the contract. This serves as a driving force to ensure a level of cleanliness in the city that is...well, fit for a king, to such a degree that the streets used for the coronation of Charles III were returned to the public on Sunday evening that same weekend.

- BARLES, Sabine. L’invention des déchets urbains : France, 1790–1970 [The Invention of Urban Waste: France, 1790-1970]. Seyssel: Éditions Champ Vallon, 2005. ↩︎

- DUEQUENNOI, Christian. Les déchets, du Big Bang à nos jours [Waste: From the Big Bang to the Present Day]. Paris: Éditions Quae, 2015. ↩︎

- CONESA, Marc, POIRIER Nicolas. “Fumiers ! Ordures ! Gestion et usage des déchets dans les campagnes de l’Occident médiéval et moderne”. Revue belge de philosophie et d’histoire, no. 98, 2020. ↩︎

- COMPAGNON, Antoine. Les Chiffonniers de Paris [The Ragpickers of Paris], Paris: Gallimard, 2017. ↩︎

- LE PLAY, Frédéric. Les Ouvriers européens [The European Workers], Paris : Hachette Bnf (2016) (Imprimerie impériale, 1855). ↩︎

- A large field used as an open-air landfill, where different types of waste dried on the ground to produce fertilizer. ↩︎

- COMPAGNON, Antoine. Les Chiffonniers de Paris [The Ragpickers of Paris], Paris: Gallimard, 2017. ↩︎

- CORBIN, Alain, The Foul and the Fragrant: Odor and the French Social Imagination, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1986. ↩︎

- GUIEN, Jeanne. Le Consumérisme à travers ses objets : Vitrines, gobelets, déodorants, smartphones… [Consumerism Through Its Objects: Display Cases, Disposable Cups, Deodorants, Smartphones…], Paris: Divergences, 2021. ↩︎

- In the context of France, a prefect is a high-ranking government official who represents the central government at the departmental level ↩︎